What's New - Timeline - Articles - Techniques - Catalog - Seminars - Links - Contact Us

The Manly Art of Quarter-Staff

Origins of a Victorian Combat Sport

By Tony Wolf

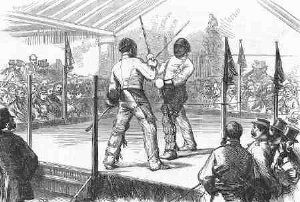

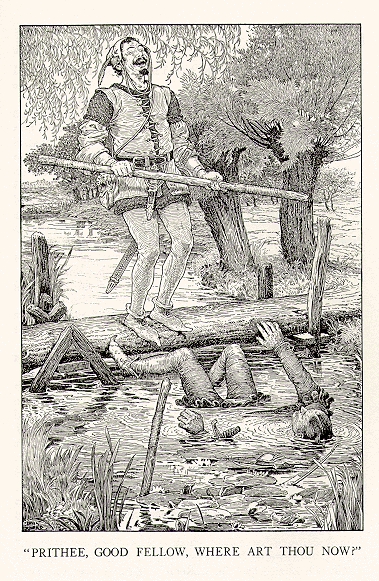

A quarterstaff match in

1870

A quarterstaff match in

1870

The late Victorian era was a time of exploration

and innovation in many fields, including the arts of self defence.

Wrestling in various regional styles and boxing according to the

rules of the London Prize Ring (later the Marquis of Queensberry

Rules) were immensely popular spectator sports. The merits of newly

introduced methods such as French Savate and la Canne, Japanese

Jiu-jitsu and the English adaptation, "Bartitsu", were

enthusiastically debated in newspaper and magazine articles. British

soldiers were still trained in combat with weapons such as the

bayonet and cavalry sabre, and research into antique methods of

swordplay was undertaken to improve their skills. In many ways, the

period between 1870 - 1900 was a Golden Age of close-combat.

The Victorian English penchant for the "manly arts" also included

quarterstaff fencing. In this sport, players wearing fencing uniforms

and protective armour competed for points by sparring with

lightweight staves, typically up to eight feet in length. Two manuals

detailing the rules and techniques were produced; Sergeant Thomas

McCarthy's "Quarter-Staff" in 1883, and a chapter of "Broadsword and

Singlestick" by R.G. Allanson-Winn in 1898. In the early 1900s,

quarterstaff fencing was taken up by members of the Boy Scout

movement, who produced a simplified manual for training towards their

"Master at Arms" badge.

This essay attempts to trace the origins and development of this

uniquely English combat sport.

In his "Paradoxes of Defence" (1599), the English

Master-at-Arms George Silver wrote:

The Short Staffe is most commonly the best weapon of all other, although other weapons may be more offensive, and especially against many weapons together, by reason of his nimbleness and swift motions, and is not much inferior to the Forest Bille, although the Forest Bille be more offensive, the Short Staffe will prove the better weapon.

|

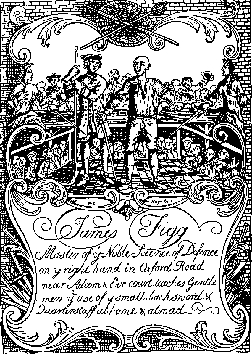

The quarterstaff was closely identified

with sport and civilian self-defence, as a weapon of

expedience used by travellers or in formal duels. By the

early 1700s the weapon was commonly employed in public

prize-fights, with the winner receiving both gate-money and

the proceeds of wagering. The famed English stage gladiator

James Figg promoted the art, along with backswording and

pugilism, in bouts at Southwark Fair, and after his

retirement from the stage in 1735 he taught it to young

aristocrats at his own School of Arms in London's Oxford

Street. |

|

In this essay, I suggest that the sport of

quarterstaff fencing as practised between 1870 and 1898 was not a

direct, lineal continuation of the traditional art, but rather a

Victorian innovation or reconstruction drawing upon three main

influences. These included the widespread availability of bamboo, the

boom in sporting equipment manufacture, and the popularity of the

Robin Hood legends. Bamboo was introduced into England around

1827. Bamboo poles were light enough that players could

strike to the body at full speed and risk only a welt or

bruise, and a slender eight-foot length was flexible enough

to absorb impact without splitting. British cavalrymen

employed bamboo training weapons in lance manoeuvres,

following the example of Indian soldiers they encountered

during the "Raj" period, beginning in 1858, and bamboo

quarterstaves are recommended in all of the surviving

Victorian-era manuals. Even armed with lightweight bamboo

weapons, the knees and shins, groin, hands, temples, throat,

and eyes were still vulnerable to serious, even if

accidental, injury. By 1870, however, amateur quarterstaff

fencers could choose from a diverse range of protective

equipment designed for other sports. By the late 1860s gladiatorial stage

combats were a thing of distant memory, and the quarterstaff

was most widely associated with the legendary outlaw hero of

Sherwood Forest.

The traditional English staff was a sturdy weapon of oak or similar

hardwood, difficult to manoeuvre with any regard for a sparring

partner's safety. It's important to remember that Figg and his

contemporaries were professional fighters, willing to risk injury in

un-armoured, full-contact bouts with weapons (although it was

suspected at the time that some professionals fixed their fights, in

the manner of modern pro-wrestlers.) The danger of fencing with oak

staves may have dissuaded amateurs from taking up the art

recreationally, in contrast to the gladiators who fought to earn

their living.

As Britain entered the Industrial Age, there arose a

relatively affluent urban middle-class with time to pursue

sports and other diversions. Supply meets demand, and the

first sporting equipment companies were established, leading

to a rapid evolution in sporting equipment design and

manufacture.

McCarthy Guard

Stance

Allanson-Winn

Guard

Between 1820 - circa 1850, the mask used by fencers (more

accurately, "foilists") had been a simple wire mesh screen

across the face. In response to the demands of heavier

weapons such as the singlestick and training bayonet, mask

designs began to incorporate hardened leather panels to

protect the top and sides of the head, or helmet attachments

woven out of strong wicker. The facial mesh was strengthened

and reinforced with an internal framework of heavy wire that

reduced denting and the chances of penetration. By the 1880s

the Army had commissioned the "military broadsword helmet"

for use in training cavalry soldiers, with additional

protection for the back of the head. This design is

recommended in both the McCarthy and Allanson-Winn

quarterstaff texts.

Broadsword (military sabre) fencers developed padded leather aprons

in a variety of styles, providing some degree of protection to the

groin area and effectively padding the thighs against cutting

attacks. At about the same time, new knee and shin guards,

constructed out of bamboo strips backed with padding, were invented

for the sport of cricket. Finally, the widespread availability of

commercially manufactured boxing gloves allowed a measure of hand and

finger protection beyond the requirements of sword fencers, but ideal

for quarterstaff players whose weapons lacked guards.

Victorian England was in the grip of Robin Hood fever, and

hundreds of books, songs, plays and poems were produced,

commemorating and elaborating his adventures.

A key incident in these stories, instantly familiar even

today, is Robin Hood's quarterstaff match with Little John,

taking place on a bridge over a shallow stream.

It is not unlikely that the recreational quarterstaff play

of the later Victorian period was influenced as much by the

popularity of the Robin Hood legends as by the memory of

Figg and his peers fighting on the stage at Southwark

Fair.

Tragically, many young English athletes gave up

their lives in the trenches of the First World War, and the

generation that might otherwise have perpetuated the new sport of

quarterstaff fencing was all but lost. Many other Victorian-era

combat arts and sports were similarly afflicted, some experiencing a

brief revival in the 1920s (such as quarterstaffing as practised by

the Boy Scouts) before finally succumbing during the Great Depression

and then World War Two. Similarly, the homogenising effect of the

international Olympic movement caused many obscure sports to fade

from memory through lack of publicity and funding. It is only in

comparatively recent years that these activities have been researched

and, in some cases, brought tentatively back to life.